Several years back I wrote about Chinese-Canadian spies trained to undergo clandestine operations in Japanese-occupied Asia. This year, one such agent caught my eye in particular, and - curiously enough - he was doing his duty for the Allies a year before the Canadian government had started its training programs...

Bill Chong, born in 1911 in Vancouver BC, was in Hong Kong trying to tie up loose ends with his late father's property in Canton. When the Japanese invaded, overran, and occupied the small British colony in 1941, he was stuck.

Chong was there to witness the horrible acts Japanese soldiers did to the local population, as well as the massacre of isolated Canadian soldiers - the first Canadians to die in the war. In his words:

"I had seen so much of the war in Hong Kong I was full of hate," he said. "I had seen how the Japanese killed people, killed Canadians without any cause. They'd just shoot anybody they want, they'd shoot people left and right."

Determined to do something about the atrocities around him, Chong escaped to China and hooked up with the British Army, planning to become a guerrilla soldier behind enemy lines. Instead, an Australian in a similar situation named Lindsay Ride convinced him to use his unique situation - a Chinese-Canadian polyglot - to better serve the war effort in military intelligence.

Bill Chong became a spy, codenamed "Agent 50".

Any time he needed to contact British Intelligence, Chong would go to the Chinese telegraph office - his only means of communication - and wire messages out with the number "50" somewhere on the message. The example he gives is a message about "going back for his mother's 50th birthday, waiting for transportation. The rest would be double-meanings and coded words to explain his situation.

Chong immersed himself in the criminal underworld of southeast Asia, in smugglers' towns and the like. He used these criminal contacts to make his way around as he underwent his missions.

His first mission was to infiltrate the Portuguese colony of Macao and find out the fate of the British consul stationed there. Macao then was neutral yet teeming with Japanese troops stopping or shooting anyone coming into the island colony. Chong eventually made his way in by paying off bandits to smuggle him into Macao, where he learned that the British consul there was okay; he returned to China to continue his work.

As Agent 50, Chong spent five years behind enemy lines, walking 50 to 80 kilometers a day, and sleeping on the ground or - on his luckier days - on the wooden floors at headquarters. He scouted Japanese movements, translated messages, transported medical supplies between posts, and even helped shot-down airmen escape back to Allied controlled territories.

His track record is rough, and while he was responsible for rescuing hundreds of Allies during the course of the war, he never kept personal records: those sorts of records on one's person would lead to a quick death if caught by Japanese patrols.

In fact, Chong had indeed been captured on three separate instances. And while he escaped all three, the terror of such moments cannot be fully expressed.

On one occasion, Chong and a traveling companion were discovered hiding from a patrol and brought out. The two were callously asked how they wanted to be killed: "be shot or have [his] head chopped off." Opting to be shot, the Japanese soldiers handed Chong and his companion shovels so they could dig their own graves. Upon tiring of the slow progress in the hard earth, one of the soldiers drew a sword and demanded they kneel down - "bullets cost money," he said.

Moments away from death, Chong's traveling companion told the soldiers - in Japanese - to look in his vest pocket. Inside was an old note the man had from his time in a Japanese school in Macao. The note was a card from a teacher there: a retired Japanese officer who had also been a master spy that taught people Japanese so that they could bring him information.

Chong and his companion were untied and released. Chong would go on to survive the war.

Bill Chong, Agent 50, had done a great duty. For his efforts, in 1946 he was awarded the Order of the British Empire, the highest military honour given to non-British citizens - he remains the only Chinese-Canadian to ever receive the honour. After the war he remained in Hong Kong as an agent for the British secret service, while working as a restaurateur for a day job.

Despite being a senior, the British government wanted him to stay on. But Chong had done enough for a lifetime, and retired to Nanaimo, BC in 1976 where he taught Chinese cooking at Malaspina College. Chong also recalls that once he returned to Canada, he found out that all his old friends had fought in Europe and was pleased to know he wasn't the only one involved in the war.

"Every time we have a meeting we have a lot of fun, a lot of jokes. That's how it should be, I guess."

As far as I know, Bill Chong is in his nineties and is still alive and well in British Columbia. As his clandestine story slowly came out of hiding, CBC has aired documentaries that feature him and he continues to be a presence in local veterans' affairs.

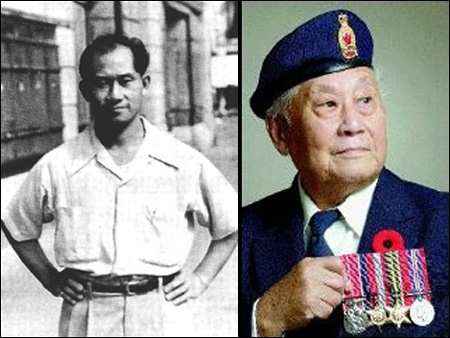

(Bill Chong, young and old)

The story of Agent 50 is remarkable for so many reasons. For one, he was volunteering for service for a country that would not have allowed him to do so for another year when the demand for "more Chinese special forces" rose - at the ever-helpful encouragement of the British government who more or less threatened to recruit Chinese-Canadians directly if they had to. For another, even if the social back story of disenfranchised minorities doing their duty for a country that didn't want them wasn't there, Chong's story of a spy behind enemy lines rescuing souls and dealing with underworld contacts leaves him as a hero in his own right.

In the past couple days I had come to learn of many amazing Chinese-Canadians - all of them second-generation, born in Canada - who went well beyond the call of duty in southeast Asia. For this year, I submit the story of Bill Chong, Agent 50, as but a single example.