"Insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results." (Albert Einstein)

Looking down a list of battles during the Second Sino-Japanese War, I'm actually finding myself surprised at how often I'm seeing battles listed with Chinese victories. It's terrible to say, but it’s true; my understanding until today was that China was on an extremely defensive war against an extremely aggressive belligerent. Still, even a successful defense counts as a victory, and suddenly the statistics begin to make a little more sense.

Now true, the battle I’m about to discuss is actually technically a Japanese victory. Nevertheless, once one takes into account the history of the battlefield and the immediate aftermath, it’s hard to not feel impressed and amazed. For this story, we go to Hunan Province in China and to the city of Changsha.

Changsha, the capital of Hunan, is a major commercial centre of China and has been since the Qin Dynasty in the 3rd century BC (today, Changsha accommodates a population of over seven million people). During the war, the Changsha region also happened to be one of the bases out of which the American Flying Tigers flew. When the Japanese invaded China early in the war, Changsha was easily on their list of cities to conquer just as much as Shanghai or Beijing. Much like Shanghai, fighting was long and grueling, and the Japanese suffered long for every mile they took. However, unlike Shanghai in 1937, when the Japanese arrived at Changsha in the autumn of 1939 they found it rather difficult to capture.

In fact, Changsha was the first major Chinese city to not fall to the Imperial Japanese Army in those early years. Despite being pushed back to the rivers and subject to the internationally criminal use of poison gas, the Chinese National Revolutionary Army cut off, encircled and ultimately devastated the Japanese forces at Changsha.

The Imperial Japanese Army returned to Changsha two years later in 1941. 120,000 Japanese troops approached and entered the city that September. Already, Chinese guerillas harried them through the mountains. Inside the city, the Japanese eventually found themselves facing off against ten Chinese regular armies and were forced to retreat after suffering over 10,000 casualties.

The Japanese were back to Changsha the following December; it was the first major Japanese offensive following the attack at Pearl Harbor. Originally planned as a means to hold back reinforcements to Hong Kong, the Third Battle of Changsha became an all-out attack after Hong Kong fell on Christmas Day. Again, 120,000 Imperial Japanese troops (along with 200 fighters and bombers) came to the large, stubborn city. Again, the National Revolutionary Army set traps and ambush points along the rivers and mountains around the city. In the end, almost 57,000 Japanese troops were lost to constant counterattacks and ambushes around the heavily defended city (to a loss of about 28,000 Chinese troops). Much like the first battle in 1939, Changsha was the lone victory against Imperial Japan during a time when they were running roughshod over the Pacific Ocean. Changsha was a city that refused to fall.

Nevertheless, as they say, all good things must come to an end. Come May 1944, Changsha was in the path of “Operation Ichigo”, a plan designed to link land and rail through the entire Asian continent from Manchuria to Southeast Asia. This time the Japanese were utterly determined to take the city, and sent 360,000 troops to do so – it was the single-largest Japanese deployment of troops of the entire conflict.

The battle can be more properly labelled “The Campaign of Changsha-Hengyang” as the neighbouring Hengyang was just as vital to Operation Ichigo as Changsha. Changsha was still the first city to be attacked, however, and the 360,000 Japanese troops arrived perhaps a little more methodically than before. Learning the lessons of three devastating defeats, the Japanese were sure to secure mountain and river paths as well as quickly outflank the defending Chinese armies before they could do the same. Outflanked, the defenders of Changsha were forced to retreat; at last, Changsha was taken by the Japanese quickly and at the relative cost of 67,000 Chinese troops and 25,000 Japanese troops.

With the fall of Changsha in June, 100,000 soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army set its sights on Hengyang. The 17,000 defenders at Hengyang, meanwhile, turned Hunan’s second largest city into the province’s largest fortress. After evacuating 300,000 inhabitants, the National Revolutionary Army built trenches, bunkers, and even man-made cliffs, and seeded every position with machine guns and artillery. With marshes and rivers protecting the city, the Japanese could only attack from the south; and when they did, they suffered dearly.

On June 22nd, the Japanese Army Air Service began bombarding the city defenses for weeks until July 2nd; Hengyang held while the Japanese scrounged for more bombs. The Japanese were again repelled on a July 11th advance to earthworks and killzones of machinegun crossfire. Japanese morale wavered as this pocket of Chinese resisters whittled at their besiegers.

It would not last. The Japanese began a vicious assault on August 4th with three divisions of reinforcements and four days of intense bombing and shelling. From 17,000 soldiers, the remaining National Revolutionary Army defenders were reduced to barely 2,000 wounded men. After 48 days of siege – the longest defense of a single city during the entire Second Sino-Japanese War – Hengyang was open for the taking.

The Japanese would go on to murder about 1,000 wounded Chinese troops in the Hengyang hospital before they would open up negotiations for terms of surrender. On August 8th, 1944, after getting the Japanese to agree to spare the remaining civilians and wounded, General Fang Xianjue – commander of the garrison – surrendered the city.

It was all still too little, too late for Japan.

The frustration of not being able to take Hengyang – especially in conjunction with the American liberation of Saipan – battered the Japanese political cabinet; with the loss of Saipan, the cabinet (including Prime Minister Tojo Hideki) were forced to resign. Military organization was stretched thin as the Japanese suffered almost 1,000 casualties to their commissioned officers alone at Hengyang. The United States Army Air Force had lost Hengyang as an airbase, but had still gained Saipan and could still attack the Japanese home islands. Though Operation Ichigo was technically a success and a rail link through the entire continent existed, there were not enough trains (and even less fuel) to make the connection useful. As for the Japanese troops themselves, though they pushed the Chinese out of Hunan, they were still surrounded around Hunan by guerillas and other National Revolutionary Army soldiers waiting to ambush them wherever they dared to go.

Japanese lines were stretched thin across the entire country, and were constantly under attack by Chinese ambushes. They were negotiating terms more and more in efforts to contain a semblance of control in a country on the verge of wiping them out. After five years and four attempts to finally take the city of Changsha, the Imperial Japanese Army in China was broken.

The tide had turned.

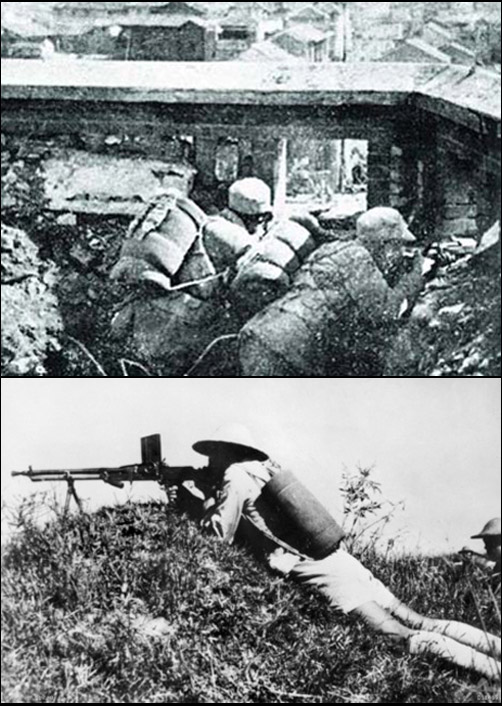

(Top: Emplacement during the First Battle. Bottom: Chinese gunner during the Third Battle.)